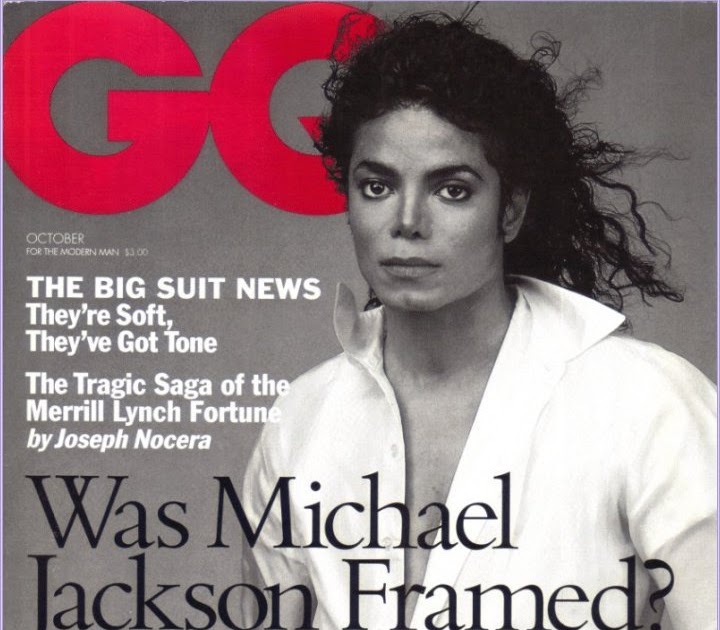

Was Michael Jackson Framed?

The Untold Story

Mary A. Fischer

GQ, October 1994

Did Michael Do It? The untold story of the events that brought down a superstar

Before O.J. Simpson, there was Michael Jackson—another beloved black celebrity seemingly brought down by allegations of scandal in his personal life. Those allegations—that Jackson had molested a 13-year-old boy—instigated a multimillion-dollar lawsuit, two grand-jury investigations and a shameless media circus.

Jackson, in turn, filed charges of extortion against some of his accusers. Ultimately, the suit was settled out of court for a sum that has been estimated at $20 million; no criminal charges were brought against Jackson by the police or the grand juries. This past August, Jackson was in the news again, when Lisa Marie Presley, Elvis’s daughter, announced that she and the singer had married.

As the dust settles on one of the nation’s worst episodes of media excess, one thing is clear: The American public has never heard a defense of Michael Jackson. Until now.

It is, of course, impossible to prove a negative—that is, prove that something didn’t happen. But it is possible to take an in-depth look at the people who made the allegations against Jackson and thus gain insight into their character and motives.

What emerges from such an examination, based on court documents, business records and scores of interviews, is a persuasive argument that Jackson molested no one and that he himself may have been the victim of a well-conceived plan to extract money from him.

More than that, the story that arises from this previously unexplored territory is radically different from the tale that has been promoted by tabloid and even mainstream journalists.

It is a story of greed, ambition, misconceptions on the part of police and prosecutors, a lazy and sensation-seeking media and the use of a powerful, hypnotic drug. It may also be a story about how a case was simply invented.

Neither Michael Jackson nor his current defense attorneys agreed to be interviewed for this article. Had they decided to fight the civil charges and go to trial, what follows might have served as the core of Jackson’s defense—as well as the basis to further the extortion charges against his own accusers, which could well have exonerated the singer.

Jackson’s troubles began when his van broke down on Wilshire Boulevard in Los Angeles in May 1992. Stranded in the middle of the heavily trafficked street, Jackson was spotted by the wife of Mel Green, an employee at Rent-a-Wreck, an offbeat car-rental agency a mile away. Green went to the rescue.

When Dave Schwartz, the owner of the car-rental company, heard Green was bringing Jackson to the lot, he called his wife, June, and told her to come over with their 6-year-old daughter and her son from her previous marriage.

The boy, then 12, was a big Jackson fan. Upon arriving, June Chandler Schwartz told Jackson about the time her son had sent him a drawing after the singer’s hair caught on fire during the filming of a Pepsi commercial. Then she gave Jackson their home number.

“It was almost like she was forcing [the boy] on him,” Green recalls. “I think Michael thought he owed the boy something, and that’s when it all started.”

Certain facts about the relationship are not in dispute. Jackson began calling the boy, and a friendship developed. After Jackson returned from a promotional tour, three months later, June Chandler Schwartz and her son and daughter became regular guests at Neverland, Jackson’s ranch in Santa Barbara County.

During the following year, Jackson showered the boy and his family with attention and gifts, including video games, watches, an after-hours shopping spree at Toys “R” Us and trips around the world—from Las Vegas and Disney World to Monaco and Paris.

By March 1993, Jackson and the boy were together frequently and the sleepovers began. June Chandler Schwartz had also become close to Jackson “and liked him enormously,” one friend says. “He was the kindest man she had ever met.”

Jackson’s personal eccentricities—from his attempts to remake his face through plastic surgery to his preference for the company of children—have been widely reported. And while it may be unusual for a 35-year-old man to have sleepovers with a 13-year-old child, the boy’s mother and others close to Jackson never thought it odd. Jackson’s behavior is better understood once it’s put in the context of his own childhood.

“Contrary to what you might think, Michael’s life hasn’t been a walk in the park,” one of his attorneys says. Jackson’s childhood essentially stopped—and his unorthodox life began—when he was 5 years old and living in Gary, Indiana. Michael spent his youth in rehearsal studios, on stages performing before millions of strangers and sleeping in an endless string of hotel rooms.

Except for his eight brothers and sisters, Jackson was surrounded by adults who pushed him relentlessly, particularly his father, Joe Jackson—a strict, unaffectionate man who reportedly beat his children.

Jackson’s early experiences translated into a kind of arrested development, many say, and he became a child in a man’s body.

“He never had a childhood,” says Bert Fields, a former attorney of Jackson’s. “He is having one now. His buddies are 12-year-old kids. They have pillow fights and food fights.”

Jackson’s interest in children also translated into humanitarian efforts. Over the years, he has given millions to causes benefiting children, including his own Heal The World Foundation.

But there is another context—the one having to do with the times in which we live—in which most observers would evaluate Jackson’s behavior.

“Given the current confusion and hysteria over child sexual abuse,” says Dr. Phillip Resnick, a noted Cleveland psychiatrist, “any physical or nurturing contact with a child may be seen as suspicious, and the adult could well be accused of sexual misconduct.”

Jackson’s involvement with the boy was welcomed, at first, by all the adults in the youth’s life—his mother, his stepfather and even his biological father, Evan Chandler (who also declined to be interviewed for this article).

Born Evan Robert Charmatz in the Bronx in 1944, Chandler had reluctantly followed in the footsteps of his father and brothers and become a dentist.

“He hated being a dentist,” a family friend says. “He always wanted to be a writer.”

After moving in 1973 to West Palm Beach to practice dentistry, he changed his last name, believing Charmatz was “too Jewish-sounding,” says a former colleague.

Hoping somehow to become a screenwriter, Chandler moved to Los Angeles in the late Seventies with his wife, June Wong, an attractive Eurasian who had worked briefly as a model.

Chandler’s dental career had its precarious moments. In December 1978, while working at the Crenshaw Family Dental Center, a clinic in a low-income area of L.A., Chandler did restoration work on sixteen of a patient’s teeth during a single visit.

An examination of the work, the Board of Dental Examiners concluded, revealed “gross ignorance and/or inefficiency” in his profession. The board revoked his license; however, the revocation was stayed, and the board instead suspended him for ninety days and placed him on probation for two and a half years. Devastated, Chandler left town for New York. He wrote a film script but couldn’t sell it.

Months later, Chandler returned to L.A. with his wife and held a series of dentistry jobs. By 1980, when their son was born, the couple’s marriagewas in trouble.

“One of the reasons June left Evan was because of his temper,” a family friend says.

They divorced in 1985. The court awarded sole custody of the boy to his mother and ordered Chandler to pay $500 a month in child support, but a review of documents reveals that in 1993, when the Jackson scandal broke, Chandler owed his ex-wife $68,000—a debt she ultimately forgave.

A year before Jackson came into his son’s life, Chandler had a second serious professional problem. One of his patients, a model, sued him for dental negligence after he did restoration work on some of her teeth.

Chandler claimed that the woman had signed a consent form in which she’d acknowledged the risks involved. But when Edwin Zinman, her attorney, asked to see the original records, Chandler said they had been stolen from the trunk of his Jaguar.

He provided a duplicate set. Zinman, suspicious, was unable to verify the authenticity of the records. “What an extraordinary coincidence that they were stolen,” Zinman says now. “That’s like saying ‘The dog ate my homework.’ ” The suit was eventually settled out of court for an undisclosed sum.

Despite such setbacks, Chandler by then had a successful practice in Beverly Hills. And he got his first break in Hollywood in 1992, when he cowrote the Mel Brooks film Robin Hood: Men in Tights.

Until Michael Jackson entered his son’s life, Chandler hadn’t shown all that much interest in the boy.

“He kept promising to buy him a computer so they could work on scripts together, but he never did,” says Michael Freeman, formerly an attorney for June Chandler Schwartz.

Chandler’s dental practice kept him busy, and he had started anew family by then, with two small children by his second wife, a corporate attorney.

At first, Chandler welcomed and encouraged his son’s relationship with Michael Jackson, bragging about it to friends and associates.

When Jackson and the boy stayed with Chandler during May 1993, Chandler urged the entertainer to spend more time with his son at his house.

According to sources, Chandler even suggested that Jackson build an addition onto the house so the singer could stay there. After calling the zoning department and discovering it couldn’t be done, Chandler made another suggestion—that Jackson just build him a new home.

That same month, the boy, his mother and Jackson flew to Monaco for the World Music Awards. “Evan began to get jealous of the involvement and felt left out,” Freeman says.

Upon their return, Jackson and the boy again stayed with Chandler, which pleased him—a five-day visit, during which they slept in a room with the youth’s half brother. Though Chandler has admitted that Jackson and the boy always had their clothes on whenever he saw them in bed together, he claimed that it was during this time that his suspicions of sexual misconduct were triggered.

At no time has Chandler claimed to have witnessed any sexual misconduct on Jackson’s part.

Chandler became increasingly volatile, making threats that alienated Jackson, Dave Schwartz and June Chandler Schwartz. In early July 1993, Dave Schwartz, who had been friendly with Chandler, secretly tape-recorded a lengthy telephone conversation he had with him.

During the conversation, Chandler talked of his concern for his son and his anger at Jackson and at his ex-wife, whom he described as “cold and heartless.”

When Chandler tried to “get her attention” to discuss his suspicions about Jackson, he says on the tape, she told him “Go fuck yourself.”

“I had a good communication with Michael,” Chandler told Schwartz. “We were friends. I liked him and I respected him and everything else for what he is. There was no reason why he had to stop calling me. I sat in the room one day and talked to Michael and told him exactly what I want out of this whole relationship. What I want.”

Admitting to Schwartz that he had “been rehearsed” about what to say and what not to say, Chandler never mentioned money during their conversation. When Schwartz asked what Jackson had done that made Chandler so upset, Chandler alleged only that “he broke up the family. [The boy] has been seduced by this guy’s power and money.” Both men repeatedly berated themselves as poor fathers to the boy.

Elsewhere on the tape, Chandler indicated he was prepared to move against Jackson: “It’s already set,” Chandler told Schwartz.

“There are other people involved that are waiting for my phone call that are in certain positions. I’ve paid them to do it. Everything’s going according to a certain plan that isn’t just mine. Once I make that phone call, this guy [his attorney, Barry K. Rothman, presumably] is going to destroy everybody in sight in any devious, nasty, cruel way that he can do it. And I’ve given him full authority to do that.”

Chandler then predicted what would, in fact, transpire six weeks later: “And if I go through with this, I win big-time. There’s no way I lose. I’ve checked that inside out. I will get everything I want, and they will be destroyed forever. June will lose [custody of the son]…and Michael’s career will be over.”

“Does that help [the boy]?” Schwartz asked.

“That’s irrelevant to me,” Chandler replied. “It’s going to be bigger than all of us put together. The whole thing is going to crash down on everybody and destroy everybody in sight. It will be a massacre if I don’t get what I want.”

Instead of going to the police, seemingly the most appropriate action in a situation involving suspected child molestation, Chandler had turned to a lawyer. And not just any lawyer. He’d turned to Barry Rothman.

“This attorney I found, I picked the nastiest son of a bitch I could find,” Chandler said in the recorded conversation with Schwartz.

“All he wants to do is get this out in the public as fast as he can, as big as he can, and humiliate as many people as he can. He’s nasty, he’s mean, he’s very smart, and he’s hungry for the publicity.” (Through his attorney, Wylie Aitken, Rothman declined to be interviewed for this article. Aitken agreed to answer general questions limited to the Jackson case, and then only about aspects that did not involve Chandler or the boy.)

To know Rothman, says a former colleague who worked with him during the Jackson case, and who kept a diary of what Rothman and Chandler said and did in Rothman’s office, is to believe that Barry could have “devised this whole plan, period. This [making allegations against Michael Jackson] is within the boundary of his character, to do something like this.”

Information supplied by Rothman’s former clients, associates and employees reveals a pattern of manipulation and deceit.

Rothman has a general-law practice in Century City. At one time, he negotiated music and concert deals for Little Richard, the Rolling Stones, the Who, ELO and Ozzy Osbourne.

Gold and platinum records commemorating those days still hang on the walls of his office. With his grayish-white beard and perpetual tan—which he maintains in a tanning bed at his house—Rothman reminds a former client of “a leprechaun.”

To a former employee, Rothman is “a demon” with “a terrible temper.” His most cherished possession, acquaintances say, is his 1977 Rolls-Royce Corniche, which carries the license plate “BKR 1.”

Over the years, Rothman has made so many enemies that his ex-wife once expressed, to her attorney, surprise that someone “hadn’t done him in.” He has a reputation for stiffing people.

“He appears to be a professional deadbeat… He pays almost no one,” investigator Ed Marcus concluded (in a report filed in Los Angeles Superior Court, as part of a lawsuit against Rothman), after reviewing the attorney’s credit profile, which listed more than thirty creditors and judgment holders who were chasing him.

In addition, more than twenty civil lawsuits involving Rothman have been filed in Superior Court, several complaints have been made to the Labor Commission and disciplinary actions for three incidents have been taken against him by the state bar of California.

In 1992, he was suspended for a year, though that suspension was stayed and he was instead placed on probation for the term.

In 1987, Rothman was $16,800 behind in alimony and child-support payments. Through her attorney, his ex-wife, Joanne Ward, threatened to attach Rothman’s assets, but he agreed to make good on the debt.

A year later, after Rothman still hadn’t made the payments, Ward’s attorney tried to put a lien on Rothman’s expensive Sherman Oaks home. To their surprise, Rothman said he no longer owned the house;three years earlier, he’d deeded the property to Tinoa Operations, Inc., a Panamanian shell corporation.

According to Ward’s lawyer, Rothman claimed that he’d had $200,000 of Tinoa’s money, in cash, at his house one night when he was robbed at gunpoint. The only way he could make good on the loss was to deed his home to Tinoa, he told them. Ward and her attorney suspected the whole scenario was a ruse, but they could never prove it. It was only after sheriff’s deputies had towed away Rothman’s Rolls Royce that he began paying what he owed.

Documents filed with Los Angeles Superior Court seem to confirm the suspicions of Ward and her attorney. These show that Rothman created an elaborate network of foreign bank accounts and shell companies, seemingly to conceal some of his assets—in particular, his home and much of the $531,000 proceeds from its eventual sale, in 1989.

The companies, including Tinoa, can be traced to Rothman. He bought a Panamanian shelf company (an existing but nonoperating firm) and arranged matters so that though his name would not appear on the list of its officers, he would have unconditional power of attorney, in effect leaving him in control of moving money in and out.

Meanwhile, Rothman’s employees didn’t fare much better than his ex-wife. Former employees say they sometimes had to beg for their paychecks. And sometimes the checks that they did get would bounce. He couldn’t keep legal secretaries.

“He’d demean and humiliate them,” says one.

Temporary workers fared the worst.

“He would work them for two weeks,” adds the legal secretary, “then run them off by yelling at them and saying they were stupid.

Then he’d tell the agency he was dissatisfied with the temp and wouldn’t pay.” Some agencies finally got wise and made Rothman pay cash up front before they’d do business with him.

The state bar’s 1992 disciplining of Rothman grew out of a conflict-of-interest matter. A year earlier, Rothman had been kicked off a case by a client, Muriel Metcalf, whom he’d been representing in child-support and custody proceedings; Metcalf later accused him of padding her bill.

Four months after Metcalf fired him, Rothman, without notifying her, began representing the company of her estranged companion, Bob Brutzman.

The case is revealing for another reason: It shows that Rothman had some experience dealing with child-molestation allegations before the Jackson scandal. Metcalf, while Rothman was still representing her, had accused Brutzman of molesting their child (which Brutzman denied). Rothman’s knowledge of Metcalf’s charges didn’t prevent him from going to work for Brutzman’s company—a move for which he was disciplined.

By 1992, Rothman was running from numerous creditors. Folb Management, a corporate real-estate agency, was one. Rothman owed the company $53,000 in back rent and interest for an office on Sunset Boulevard. Folb sued.

Rothman then countersued, claiming that the building’s security was so inadequate that burglars were able to steal more than $6,900 worth of equipment from his office one night.

In the course of the proceedings, Folb’s lawyer told the court, “Mr. Rothman is not the kind of person whose word can be taken at face value.”

In November 1992, Rothman had his law firm file for bankruptcy, listing thirteen creditors—including Folb Management—with debts totaling $880,000 and no acknowledged assets. After reviewing the bankruptcy papers, an ex-client whom Rothman was suing for $400,000 in legal fees noticed that Rothman had failed to list a $133,000 asset.

The former client threatened to expose Rothman for “defrauding his creditors”—a felony—if he didn’t drop the lawsuit. Cornered, Rothman had the suit dismissed in a matter of hours.

Six months before filing for bankruptcy, Rothman had transferred title on his Rolls-Royce to Majo, a fictitious company he controlled. Three years earlier, Rothman had claimed a different corporate owner for the car—Longridge Estates, a subsidiary of Tinoa Operations, the company that held the deed to his home.

On corporation papers filed by Rothman, the addresses listed for Longridge and Tinoa were the same, 1554 Cahuenga Boulevard—which, as it turns out, is that of a Chinese restaurant in Hollywood.

It was with this man, in June 1993, that Evan Chandler began carrying out the “certain plan” to which he referred in his taped conversation with Dave Schwartz. At a graduation that month, Chandler confronted his ex-wife with his suspicions.

“She thought the whole thing was baloney,” says her ex-attorney, Michael Freeman.

She told Chandler that she planned to take their son out of school in the fall so they could accompany Jackson on his “Dangerous” world tour. Chandler became irate and, say several sources, threatened to go public with the evidence he claimed he had on Jackson.

“What parent in his right mind would want to drag his child into the public spotlight?” asks Freeman. “If something like this actually occurred, you’d want to protect your child.”

Jackson asked his then-lawyer, Bert Fields, to intervene. One of the most prominent attorneys in the entertainment industry, Fields has been representing Jackson since 1990 and had negotiated for him, with Sony, the biggest music deal ever—with possible earnings of $700 million. Fields brought in investigator Anthony Pellicano to help sort things out. Pellicano does things Sicilian-style, being fiercely loyal to those he likes but a ruthless hardball player when it comes to his enemies.